Foreign Coins Minted in San Francisco

by Paul V. Turner

2020 Third Place

Fig 1. Philippines 50-Centavos 1907–S

When I collected coins as a child, in the 1950s, I was fascinated by several Philippine coins that had been given to the family by a relative, which bore the "S" mark of the San Francisco mint. (Fig. 1) Recently, having taken up coin collecting again, I became interested in coins produced by U.S. mints for foreign countries, and I decided to focus on those produced in San Francisco — in order to make the project easier to manage, and because I have a special interest in San Francisco's Old Mint.

Fig 2. Australia Florin 1942–S

A U.S. Congressional act of 1874 authorized the Bureau of the Mint to strike coins for foreign countries, and from 1876 to 1983 the U.S. mints produced coins for about forty countries (with only one produced since then, for Iceland in 2000). Most of the coins were made by the Philadelphia mint, but many were minted in San Francisco — for over twenty countries. There were various reasons why countries contracted with a U.S. mint to produce coins: either a country didn't have the facilities to produce its own coins, or a particular type of coin; or a country needed more coins, for a particular year, than it could produce itself; or a country was at war or occupied by an enemy force, and a government-in-exile wanted to produce coins. As a result, there were a large number of these situations during, and just after, the Second World War.

Fig 3. El Salvador 1-Centavo 1928–S

There were also several different scenarios for how the process of minting foreign coins worked. Sometimes the dies were provided by the foreign countries, sometimes by the U.S. mint (and the dies might be made in San Francisco, or in Philadelphia and sent to San Francisco). And the design of the coins might be done by the foreign country or by the U.S. mint. And sometimes three (or more) countries might be involved in the process, in various capacities.

The first challenge for me was simply to identify which coins had been minted in San Francisco. For this I used several publications: Foreign Coins Struck at United States Mints, by Charles Altz and E. H. Barton, published in 1964. Various editions of the Krause catalogs. The annual reports of the Director of the U.S. Mint. A Bureau of the Mint publication of 1981, Domestic and Foreign Coins Manufactured by Mints of the United States. And various lists and articles I found online. But these sources differ in the types of information they provide, and in some cases they disagree on which coins were produced by which mint. As a result, determining exactly which foreign coins had been produced by the San Francisco mint turned out to be more difficult than I had expected.

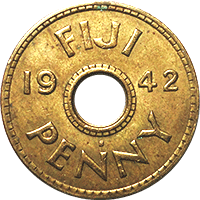

Fig 4. Fiji Penny 1942–S

The annual reports of the U.S. Mint might be assumed to have the definitive information. But these reports can be inconsistent in the data they provide, especially in the late 19th and early 20th century — sometimes noting, for example, only that the U.S. mints produced a particular coin for a foreign country, but not identifying the mint or mints. Moreover, these reports do not indicate cases where a foreign coin produced by one or more U.S. mints was also minted at the same time by the foreign country (or a different foreign country) — information which naturally is essential if one wants to be certain that an individual coin was in fact minted in San Francisco. The Krause catalogs generally provide this kind of information, but there are many cases where they neglect to specify that a coin was produced by a U.S. mint. Altz and Barton's book seems to give the most complete information, both about which U.S. mints produced foreign coins and which of the coins were also produced by foreign countries; but since the book was published in 1964, the situation after this year is less well documented, with more uncertainly about which coins were minted where.

Fig 5. French Indo-China

20-Centimes 1941–S

The easiest cases, of course, are those in which coins that are said to have come from San Francisco also bear the "S" mint mark. (It should be pointed out that the "S" alone is not necessarily sufficient evidence; in Australia, for example, it has been used by the Sydney mint.) Of the roughly 370 coins minted in San Francisco for foreign countries (counting each year as a separate coin), about 120 have the "S" mint mark. Examples include the following: Australia: 3 pence, 6 pence, shilling, and florin, 1942-44. El Salvador: 1 centavo, 1928 (the only Salvadoran coin to bear a U.S. mint mark). Fiji: half penny, penny, 6 pence, shilling, and florin, 1942-43. French Indo-China: 10 and 20 centimes, 1941. The Netherlands: 10 cents, 1944. Netherlands East Indies: 1 cent, 1/10 guilder, and 1/4 guilder, 1941–45. (An unusual characteristic of the Netherlands and Netherlands East Indies coins is that the "S" is placed at a 45-degree slant.) Peru: 5, 10, and 20 centavos, and half sol, 1942-43. The Philippines: 1, 5, 10, 20, and 50 centavos, and 1 peso, 1908-20 (when the Philippines were a U.S. terrritory); 1, 5, and 50 centavos, 1944–45 (the Commonwealth period); and the General McArthur commemorative 50-centavo and peso coins of 1947 (the Philippine Republic). (Figs. 2-9)

Above: Fig 6. The Netherlands 10-Cents 1944–S; Fig 7. Netherlands East Indies 1/10-Guilder 1942–S; Fig 8. Peru Half-Sol 1942–S

Below: Fig 9. Philippines, Peso (Gen. McArthur commemorative) 1947–S obv/rev; Fig 10. Hawaii Dollar 1883 (S)

In most cases, however, the San Francisco-minted coins do not bear mint marks. And here there are various ways of knowing (with different degrees of certainty) where they were minted. First, there are well documented cases, such as the Hawaiian coins of 1883 bearing the image of King Kalakaua (the first foreign coins struck in San Francisco), where the facts are well known, with details such as the role of the sugar-magnate Claus Spreckels, who acted as an agent between the Hawaiian government and the San Francisco mint. (Fig. 10)

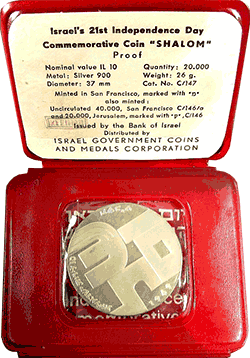

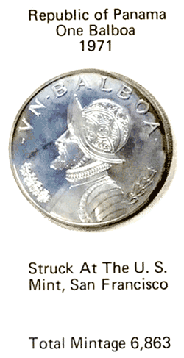

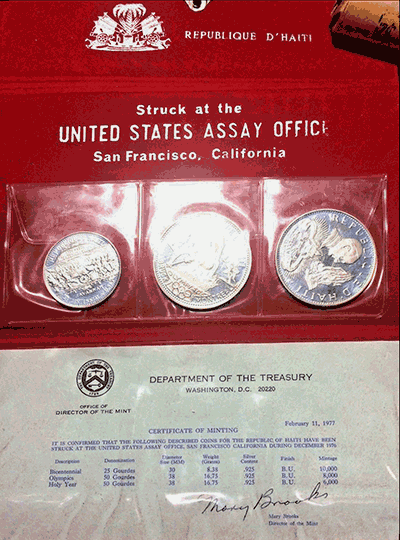

Fig 11. Israel 10-Lirot 1969(S) in original packet; Fig 12. Panama Balboa 1971(S) on mintage card

Fig 13. Haiti set of 3 1976(S) coins in original packet

Or the coins may have been issued with the information of where they were minted — for example, an Israeli 10-lirot coin of 1969, which came in a packet identifying it as having been "Minted in San Francisco." (Fig. 11) Or a Panamanian 1-balboa coin of 1971, which came with a card saying "Struck at the U. S. Mint, San Francisco." (Fig. 12) Or a group of three Haitian coins, of 1976, which were issued with a Treasury-Department certificate saying they were "Struck at the United States Assay Office, San Francisco." (Fig. 13)

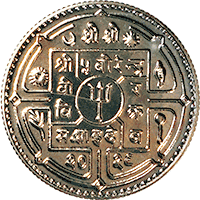

Another scenario is that all the sources simply agree that a coin was minted in San Francisco. Examples include several Colombian coins of the 1930s and 1940s; two Guatemalan coins of 1944; and several Costa Rican coins of the 1960s. But there are quite a few cases where, as mentioned earlier, the sources do not agree. This is found especially after 1964 (the year the Altz and Barton book was published), when the Krause catalogs and the Bureau of the Mint's 1981 publication often have differing information, especially with the coins of certain countries, such as Liberia, Haiti, and Nepal — the Mint publication saying that many of the coins were minted in San Francisco, while the Krause catalog doesn't specify the mint. (Figs. 14–16)

Fig 14. Liberia Dollar 1969(S); Fig 15. Haiti 50-Gourdes (Holy Year commemorative) 1976(S);

Fig 16. Nepal Rupee 1972/Nepalese year 2029(S)

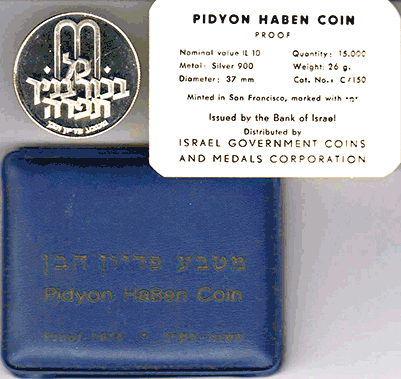

Figure 17. Israel 10-Lirot (Pidyon Haben) 1970(S), with original packet and card

This is perhaps not surprising, as the Krause catalogs often omit details simply to save space. More puzzling are cases where it is the 1981 Mint publication that leaves out information. For example, it doesn't mention a 10-lirot Israeli "Pidyon Haben" coin of 1970, although the coin was issued with a card stating that it was minted in San Francisco. (Fig. 17) (In this case, however, the coin did appear in the Mint's annual report of that year.)

A different scenario is that a foreign coin was minted by more than one U.S. mint, or by one or more U.S. mints and also by the foreign country (or occasionally a third country) — and therefore it is impossible to know which mint an individual coin came from. Examples include several Mexican coins of 1906-07, minted both in San Francisco and in Mexico City and bearing the "M" mint mark because the dies were supplied by the Mexican mint.

Figure 18. El Salvador Peso 1908 (left) and 1909 (right), lines note differences in the bust

Fig 19. El Salvador Peso 1909(S)

In some of these cases, however, there may be slight differences between the coins minted in the foreign country and in the U.S. An example is a one-peso coin of El Salvador, which has two nearly-identical varieties — one of the differences being in the width of Christopher Columbus's shoulders in the obverse image. (Fig. 18) One of the varieties was struck in San Salvador and three European mints; the other one (with wider shoulders) was struck in San Francisco in 1904 and 1909, in Philadelphia in 1914, and in both San Francisco and Philadelphia in 1911. (Fig. 19) One can therefore determine that an individual coin was struck in San Francisco only if it is of the U.S.-minted variety (with the wider-shouldered Columbus), and is of 1904 or 1909.

Figures 20. French Indo-China Centime 1920(S), and 21. French Indo-China Piastre 1921(S)

Several French Indo-Chinese coins provide further examples. A one-centime piece of 1920 was minted in both Paris and San Francisco, with the French version bearing the "A" mark of the Paris mint, and the San Francisco version having no mint mark. (Fig. 20)

A one-piaster coin of 1921–22 was minted both in Heaton in England with the "H" mint mark, and in San Francisco with no mint mark. (Fig. 21)

Figures 22. French Indo-China 10-Centimes 1940(S), and 23. French Indo-China 10-Centimes 1941–S

A 1940 ten-centime coin, according to Altz and Barton, was minted only in San Francisco, although "it bears the Paris mint mark A, since the dies were sent from the Paris mint to San Francisco." (Fig. 22) This is not quite accurate; the coin does not bear the "A," but it does have Paris privy marks — a cornucopia and a wing symbol. The following year, these Paris marks were replaced by the San Francisco "S." (Fig. 23) Apparently the San Francisco mint was using the Paris die in 1940, but in 1941 had a new die with the "S" on it.

Fig 24. Panama Balboa 1934(S)

A somewhat different case is a one-Balboa Panamanian coin of 1934, which both the Bureau of the Mint publication and Altz and Barton's book say was minted in San Francisco. (Fig. 24) The Krause catalog doesn't specify the mint, but it has a rather cryptic note in the listing of another Panamanian coin (a 50-centésimo piece of 1904–05), saying:

One million of both the 1904 and 1905 dates were melted in 1931, for the metal to issue one-Balboa coins at the San Francisco Mint.

The catalog does not specify that this was the 1-Balboa coin of 1934, but it no doubt was.

Finally, another intriguing case is a 1949 restrike of a Mexican peso of 1898. (Fig. 25) According to Altz and Barton, the restrike was produced by the San Francisco mint and was identical to the 1898 original, "with one small difference. On the pesos actually struck in 1898, there are 139 denticles in the border on the reverse, while the 1949 restrikes have only 131 denticles. This is the only U.S.-struck coin of Mexico which can be identified without doubt as originating in the United States." The Bureau of the Mint publication states that the San Francisco mint produced a Mexican peso in 1949 but doesn't specify that it was a restrike of an 1898 coin. The Krause catalog for the 19th century, in its listing of the 1898 peso, notes that there was a restrike of it in 1949, "with 134 beads" on the reverse (not the 131 stated by Altz and Barton), but doesn't say where it was minted. The story, in fact, is a good deal more complicated than any of these contradictory sources suggest.

Fig 25. Mexico Peso 1898

(restrike of 1949)

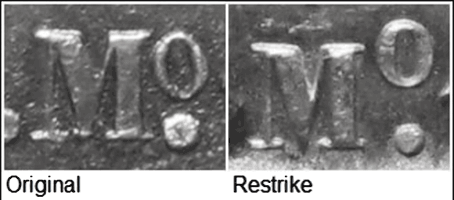

As described in an online article on the BrianRxm website, the 1949 restrike was accomplished at both the Mexican and San Francisco mints, mainly with the purpose of supplying silver coins for the Nationalist government of China, which needed them to pay its soldiers fighting the Communists. The Mexican mint could not produce enough of them; with the approval of the U.S. government, it arranged for the San Francisco mint to strike two million of them, using the new dies that had been made in Mexico. The restrikes could be distinguished from the originals, but not by the "denticles" or "beads" around the border (since these apparently varied, both in the originals and the restrikes). The difference was in the "Mº" mintmark — the "o" being placed higher in the restrikes. (Fig. 26)

Many of the coins restruck at the Mexican mint were sent to China, but the San Francisco restrikes had a different fate. According to the website article, "Two million silver pesos were struck at the San Francisco mint from June to August 1949 and were taken to the vaults of the nearby Bank of America, to await shipment to China. [But] China fell to the Communists and the pesos were no longer needed, [so] the coins were sold back to the San Francisco mint, melted, and recycled into American coins. No San Francisco pesos were saved."

Fig 26. Comparison of Mexico City mintmarks on

original 1898 Pesos and 1949 restrikes

When I presented this information in a talk to a PCNS meeting in February, 2020, one of the attendees said he knew that a few of the San Francisco restrikes did, in fact, survive. It appears, therefore, that none of the published sources of information about this coin is entirely accurate. This is another remarkable twist in the story of foreign coins minted in San Francisco. The subject is indeed more complex than most people might imagine at first.

References

Altz, Charles G. and E. H. Barton, Foreign Coins Struck at United States Mints (Racine, WI: Whitman Publishing Co., 1965).

Annual Report of the Director of the Mint (various years).

Domestic and Foreign Coins Manufactured by Mints of the United States, 1793-1980 (Washinton: Bureau of the Mint, 1981).

Krause and Mishler, Standard Catalog of World Coins: 20th-century (47th ed.), 19th-century; Latin American ed. (2002).