We Don’t Trust Our Doll-ar:

The Standard Theatre Souvenir

by William D. Hyder

We Don’t Trust Our Doll-ar. As a collector of so-called dollars, not to mention California tokens and medals from the 1800s, that inscription caught my eye. The 1885 dated medal itself was fairly well beat up being a soft white metal, perhaps even a lead alloy of some sort, and crudely holed in the distant past. The 2x2 in which it was stored said the Standard Theatre named on the obverse was a San Francisco establishment. A quick Google search confirmed the presence of a Standard Theatre in San Francisco (despite the British spelling of theater). The lure of a possible story was too good to pass up and I managed to acquire it for my collection.

Figure 1: The Standard Theatre souvenir. White Metal, 38mm

The obverse portrait of a well-groomed, mustached gentlemen in the typical business dress of the day with the high collar, likely a silk ascot, and a high button Morning Coat. While it appears to be a dapper stereotypical figure of a theater manager, the image is likely that of Charley Reed who is named on the reverse. The legend arched above in two lines reads, STANDARD THEATRE SOUVENIR / CHAS W. CORNELIUS. MANAGER. Seven stars border each side of the date, 1885, below.

Figure 2: Charley Reed

1911 photograph from Rice

The reverse statue of an apparent thespian with raised right arm and script in left hand stands atop a pedestal with rays of light fanned out behind him. The legend above in two lines reads, CHARLIE REED’S MINSTRELS / WE DON’T TRUST / OUR DOLL-AR (the intriguing legend continues below the pedestal).

The San Francisco Theaters blog reviews the history of the city’s many theaters and opera houses including the Standard Theatre. The building opened in 1865 as the Congress Hall followed by multiple closings, re-openings, remodels, and further business failures. The last iteration of the opera/minstrel venue, the Standard Theatre, reopened on October 28, 1878 under the management of M. A. Kennedy. The theater building burned in 1889 and was not rebuilt.

Many theaters devoted their shows to minstrels combined with a healthy dose of burlesque. What might be called an opera typically combined music and comedy with fancy, albeit scantily clothed women. By the beginning of the 1880s, the shows had become stale and interest was waning. Attempts at revival of audience interest ranged from improving quality of the humor and music to exposing more female skin.

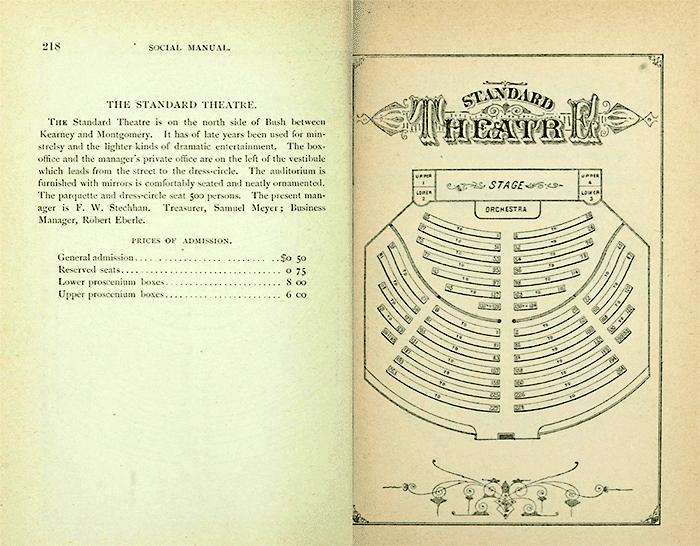

Figure 3: The Standard Theatre floor plan as published in the 1884 San Francisco Social Manual.

A May 21, 1884 ad in the San Francisco Examiner for Emerson’s Standard Theatre lists F.W. Stechhan and C.W. Cornelius as managers. Ownership, lease holders, and management appears confused as names change, manager designations change, and different owners are indicated in newspaper articles. It seems financial problems produced turmoil and churn in financial backers. For example, popular San Francisco minstrel star Billy Emerson transformed his run at the theater into some form of ownership, leasehold, or other financial involvement with the theater. An Examiner ad on June 9, 1883 lists Emerson as the sole proprietor and manager of the “Coolest Theater in the city.” That same ad notes that the Standard Theater would close while Emerson leased the Bush-Street theater and performed there with his minstrel company.

The Sacramento Daily Union reported on January 13, 1885 that the Standard Minstrel Company filed incorporation papers for the purpose of conducting, managing, and controlling the Standard Theater in San Francisco. The directors included John J. McBride, Frank W. Stechhan, Charles W. Cornelius, Samuel Myers, and William P. Adams who divided 15,000 shares of capital stock valued at $1.00 a share among themselves.

A month after filing the incorporation papers for the Standard Minstrel Company, Cornelius was in Portland, Oregon. He was born on the outskirts of Portland in North Plains on October 11, 1856 making him a native Oregonian. The Morning Oregonian reported on February 23, 1885 that Cornelius was visiting from San Francisco with a “great scheme for the establishment of a new and thoroughly first-class theater in this city.”

The National Register of Historic Places nomination form for the Cornelius Hotel in Portland includes a brief biography of the man who built it, and for which the hotel is named (Tess 1985). Before his involvement with the theater business in San Francisco, he ran a drugstore in Spokane, Washington returning to Portland in 1882 to purchase and run the Cornelius Bros. Drugstore. In 1886, a Portland City Directory listed his profession as an actor. After a brief stint gold mining in southern Oregon, he enrolled in medical school, graduating in 1889. In addition to his medical practice, Cornelius travelled to Alaska to mine gold and later managed the Cornelius Hotel while maintaining his medical practice. He died on November 2, 1923 after leading a full and varied life.

In the August 2, 1885 issue of the San Francisco Examiner, a theater reviewer panned a Standard Theatre’s minstrel troop’s performance of “A Cold Day When We Got Left” writing,

“Worse companies and worse pieces have been seen here and some of them have made money, but the day for this sort of thing is passing rapidly.”

In the same issue they noted that “Charles Cornelius left for New York on Tuesday to engage a first-class minstrel combination for the Standard Theater.” The plans were for the new company to open in Portland on August 31 while in route for a San Francisco debut on September 12. Later in the same article, it was noted that the longtime treasurer Sam Meyers of the Standard Theatre would be leaving August 10. The August 9, 1885 San Francisco Examiner theater review reported that F.W. Stechhan had retired from the Standard Theater management and would be replaced by Messers. Cornelius and McBride.

Cornelius and McBride apparently made plans to revitalize the Standard Theatre and those plans attracted the interest of the venue’s stalwart performer Charley Reed. The Examiner’s September 20, 1885 theater column reported that Reed would not move to the East with a new minstrel troop, opting instead to become involved with Cornelius and McBride in managing the theater.

Charley Reed—Just the Plain Comedian—as he was known, was born in New York City on May 22, 1858 and died in Boston on November 21, 1892. Rice (1906) summarizes Reed’s biography in an early book covering the minstrels. Charley Reed began and ended his career in white-face. His performances as a comedian and minstrel took him to San Francisco in 1872 with side trips to Cincinnati, Australia, and Philadelphia before partnering with Emerson’s Minstrels at the Standard Theatre. He later appeared under his own name as Charley Reed’s Minstrels and headlined at the Standard Theatre until April 10, 1886. He then moved back to the East coast for the remainder of his career.

The October 11, 1885 issue of the Examiner noted the Standard Theatre was being redecorated and painted under the direction of Reed and McBride in anticipation of the the reopening featuring new acts brought in by Cornelius from Chicago. The Daily Alta California October 19, 1885 issue carried the announcement of the grand re-opening of the Standard Theatre featuring Reed’s Minstrels among other acts.

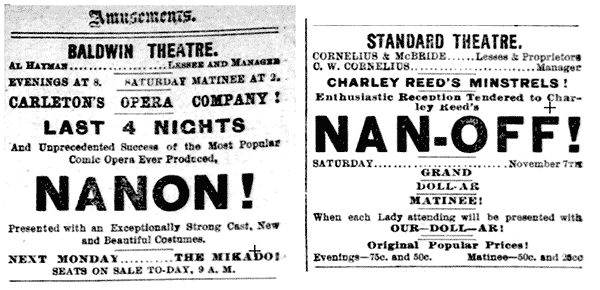

It seems from my reading of the theater reviews that Charley Reed in his new headline status applied his comedic skills to spoofing the headline performances at rival theaters. For example, the Baldwin Theater was performing a European comedy opera, Nanon. Nanon, the Mistress of the Golden Lamb was a revival of a comedic opera set in 1685, the time of Louis XIV, the Sun King (Traubner 2003). Nanon is the pretty hostess of the Golden Lamb Inn, made famous when the king praised her wine. She becomes the lover of a member of the royal court posing as a simple drummer boy. When Nanon insists on marriage, her lover arranges to have himself arrested at the altar since he is promised to another member of the royal court. The two women appeal to Louis VIV in scheming to have their shared suitor released not knowing they are both betrothed to the same man. As with any comedy, all ends well.

Figure 4: Theater ads from the November 5, 1885 Daily Alta California.

Competing ads in the November 5, 1885 Daily Alta California highlight Reed’s comedic strategy. As the Nanon is ending its run at the Baldwin, Charley Reed’s Nan-off is opening at the Standard Theatre. Somewhat later, while Macbeth is playing at the California Theater, Reed counters with McBreath.

So, what does all this have to do with the Standard Theatre souvenir? As the November announcement states, Nan-off opened on Saturday, November 7 with a “Grand Doll-ar Matinee!” Each “Lady attending will be presented with OUR—DOLL—AR.” Matinee prices were 50¢ and the evening performances were 75¢, so it appears the souvenir was a special issue for the Grand Doll-ar opening matinee. No doubt the French dolls revealed an abundant amount of skin in their scandalous French costumes. Why do they not trust “our doll-ar?” I suspect the “dolls” at the center of the Reed’s story engage in some underhanded feminine antics in their pursuit of the same beau. And, I suspect the rays behind the pedestal are an allusion to the excesses of the royal court of the Sun King.

Sources

Newspapers

- Daily Alta California

- Morning Oregonian

- Sacramento Daily Union

Internet

- Counter, Bill (retrieved March 25, 2020) “Standard Theatre” sanfranciscotheatres.blogspot.com/2019/05/standard-theatre.html.

- Tess, John M. (1985) National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form. Cornelius Hotel. npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/4111105e-b3a6-4962-823e-1c9d7e73ceea.

Publications

- — (1884) A Social manual for San Francisco and Oakland. The City Publishing Company, San Francisco.

- Rella, Ettore (1940) San Francisco Theatre Research Volume 14, A History of Burlesque. Volume XIV of A Monograph History of the San Francisco Stage and Its People from 1849 to the Present Day. Edited by Lawrence Estavan. Works Project Administration. City and County of San Francisco Project 10677.

- Rice, Edward LeRay 1911 Monarchs of Minstrelsy, from “Daddy” Rice to Date, Kenny Publishing Co., New York City, New York.

- Traubner, Richard 2003 Operetta: A Theatrical History Routledge, New York.